References to Male-Male Corporal Punishment in Wagner’s Die Meistersinger

By HisRoyalHeinie

For some, the musical world of Richard Wagner is a sadly reductive, albeit enjoyable, Bugs Bunny cartoon featuring Viking hats, spears, and fat ladies singing. For others, his operas are nothing less than transcendent, a glimpse of the sublime.

Wagner’s sole comedy, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Mastersingers of Nuremberg), from 1868, recreates the story of Hans Sachs, the real-life shoemaker-poet of sixteenth-century Nuremberg. Sachs plots to rig the outcome of his town’s annual Midsummer singing competition in favor of his new friend, Walther von Stolzing, who desires as his prize the hand of the town beauty, Eva.

Clocking in at somewhere between five and six hours, Die Meistersinger requires at least seven expert soloists and dozens more chorus and orchestra members operating at the height of their powers. Critic and scholar H.L. Mencken called it “the greatest single work of art ever produced by man,” and added, “It took more skill to plan and write it than it took to plan and write the whole canon of Shakespeare.” The libretto is impressively written in an irregular rhyme scheme known as “Knittelvers,” which would have been fashionable during the mid-1500s, the opera’s historical setting.

Spanking enthusiasts may be drawn to Wagner’s masterpiece for a different reason. Indeed, the opera contains multiple and explicit references to male-male corporal punishment, especially punishment by strap, recurring on several occasions. Hardly innuendo, these passages contribute significantly to the development of the character of David, apprentice to Hans Sachs. Most likely in his teens, David is the quintessential amorous youth; his quick tongue and hot temper find him in constant trouble. We soon learn that flogging him is apparently the only effective way of keeping him in line.

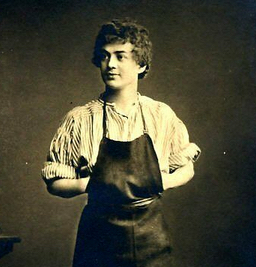

Julius Lieban as David, circa mid-1880s.

Early on, in Act I, Scene 2, David’s fellow apprentices describe him in this way:

Was der sich dünkt! Der Lehrling’ Muster!

Das macht, weil sein Meister ein Schuster!

Bei’m Leisten sitzt erm it der Feder.

Bei’m Dichten mit Draht und Pfriem.

Sein’ Verse schreibt er auf rohes Leder.

Das, dächt’ ich, gerbten wir ihm!

(How cocky he is! The model apprentice!/ That’s because his Master’s a cobbler!/ At his last he sits with a quill,/ at his poeticizing, with thread and bodkin,/ His verses he writes on raw leather/ which, methinks, we tanned for him!*)

Even in Wagner’s time, the mention of leather in this context would offer double entendre. As the scene unfolds, David gives Walther, the Romantic hero, a crash course in poetry and song. His spirited monologue concludes as such:

Trotz grossem Fleiss und Emsigkeit,

ich selbst noch bracht’ es nicht so weit,

so oft ich’s versuch’, und ’s nicht gelingt,

die “Knieriem-Schlag” – was der Meister

mir singt.

(Despite great industry and keenness,/ I myself haven’t yet got so far./ Whenever I attempt it and don’t succeed,/ my Master sings me the “Knee-strap stroke” melody.)

“Knieriem” (“Knieriemen,” plural), literally “knee strap” or “knee belt,” were intended to connect shorts and socks in one version of the traditional Bavarian costume.

David’s fellow apprentices continue to tease him mercilessly:

Der “Schlag”-reime fest er inne hat,

“Arm’-Hunger”-Weise singt er glatt;

doch die “harte-Tritt”-Weis’ die kennt er am best’,

die trat ihm der Meister hart und fest!

(He’s got the “blow” rhymes down pat,/ he sings the “poor and hungry” melody very smoothly;/ “but the “hard kick” melody is the one he knows best,/ his Master has kicked that one into him good and proper!”)

Gustav Werner as David in the early 1900s. Observe his old-fashioned ruler, a stage prop

Gustav Werner as David in the early 1900s. Observe his old-fashioned ruler, a stage prop

which Schenk later exploited for specifically CP-related purposes in his production.

At this point in the action, David is carrying a ruler, on which is attached a string and a piece of chalk, so that he can measure out the Marker’s Box being built for the Masters. In Otto Schenk’s meticulously researched and vividly realized production for New York’s Metropolitan Opera, in 2001, two apprentices grab the ruler and literally pantomime giving and receiving a spanking as they sing the “hard kick” verse.

Wagner aficionados have enjoyed numerous revivals of Die Meistersinger in this century.

Matthew Polenzani was the original David in Schenk’s superlative production. Note that

the ruler is once again part of the character’s iconography.

Hans Sachs makes his entrance in Act I, Scene 3, and wastes no time making a blatant threat toward David: “Juckt dich das Fell?” (“Is your hide itching?”)

Paul Appleby, who portrayed David in a recent revival at the Metropolitan in 2014, spoke about his approach to the character, as well as the opera’s conspicuous references to corporal punishment, in an interview for Opera Lively:

“I think [David] is probably a late teenager which is to say somewhere in between 17 and 19…A 19-year-old in 16th century Germany had a lot more expected of him and was thought of as much older and more mature person than a 19-year-old person in today’s society. Even though that sounds young, someone that old in that time period is actually well past the demarcation of adulthood. He is certainly one of the oldest, if not the oldest of the apprentices. In my approach to the role I try to make him a little less boyish and naïve. Particularly, I try to manifest this in the relationship with Hans Sachs whereby he is very much like a father figure to David. There is also an element of some kind of roughness and violence in that relationship. One of the first things that Hans Sachs says to David when he comes on stage and speaks out of turn is that he threatens to beat him, and not in a cute way. It’s quite violent. David is always getting in fights. Throughout the piece there are these strings of violence. The end of Act II is a big brawl in the town. David’s engagement with this when he is wrestling with the other apprentices is not childish or playful. There is an element of intense pugnaciousness going on, here. I took that into account when I thought about David.”

At the beginning of the third act, David and Sachs have a duet alone together onstage. During the scene, David addresses both Sachs and the audience. Upon entering, David asks Sachs if he had called for him, receiving no reply.

Er tut, als säh’ erm ich nicht?

Da ist er bös’, wenn er nicht spricht.

(He’s pretending he hasn’t seen me./ It means he’s angry when he doesn’t speak.)

Andreas Joeggi, a handsome David at Dortmund, 1988

Andreas Joeggi, a handsome David at Dortmund, 1988

David begs Sachs’s forgiveness for causing such a ruckus the evening before, admitting that he acted foolishly because he is in love with Magdalene.

Kenntet ihr die Lene, wie ich,

dann vergäb’t ihr mir sicherlich.

Sie ist so gut, so sanft für mich,

und blickt mich oft an, so innerlich:

wenn ihr mich schlagt, streichelt sie mich…

(If you knew Lena as I do,/ you would forgive me for sure./ She is so good, so gentle to me,/ and often looks at me so tenderly:/ when you strike me, she caresses me…)

When Sachs finally speaks, he asks David to recite a poem, prompting another aside to the audience: “Setzt nichts! der Meister ist wohlgemut!” (No thrashing! the Master is in a good mood!)

After what is undoubtedly the gentlest moment between the apprentice and his master, David kisses Sach’s hand. Before he leaves, he discloses:

So war er noch nie, wenn sonst auch gut!

Kann mir gar nicht mehr denken, wie der Knieriemen tut!

(He’s never been like this before, though he’s usually kind! I can’t remember what the strap’s like!)

Today we may interpret David’s claim that Sachs is “usually good” as a sign of battered person syndrome. Thoughtful listeners will likely hear something less sinister in Wagner’s music. One mustn’t forget that the story is a comedy. The ending is, in fact, so intoxicatingly joyful that it’s difficult to leave the opera house contemplating David’s journey as something akin to triggering, post-traumatic stress.

Theatergoers are often quick to judge certain works of art by their own ethical codes. Not that long ago, Sachs’s disciplining of David would have been considered the right and proper thing to do. In accordance with their accepted value system, Sachs may sincerely hit David “because he loves him.”

While there is no evidence to suggest that Wagner was a spanking fetishist, present-day spankos may elucidate the Sachs-David pairing as one of clear dominance and submission, whether or not it is by design.

David Portillo as David and Gerald Finley as Sachs, at Glyndebourne in 2016.

For further reading on Die Meistersinger, please consult M. Owen Lee’s Wagner and the Wonder of Art.

*English translations by Peter Branscombe